AND1 and the power of positioning

And making it a fair fight as a new brand.

In the late 90s, basketball looked like a closed category.

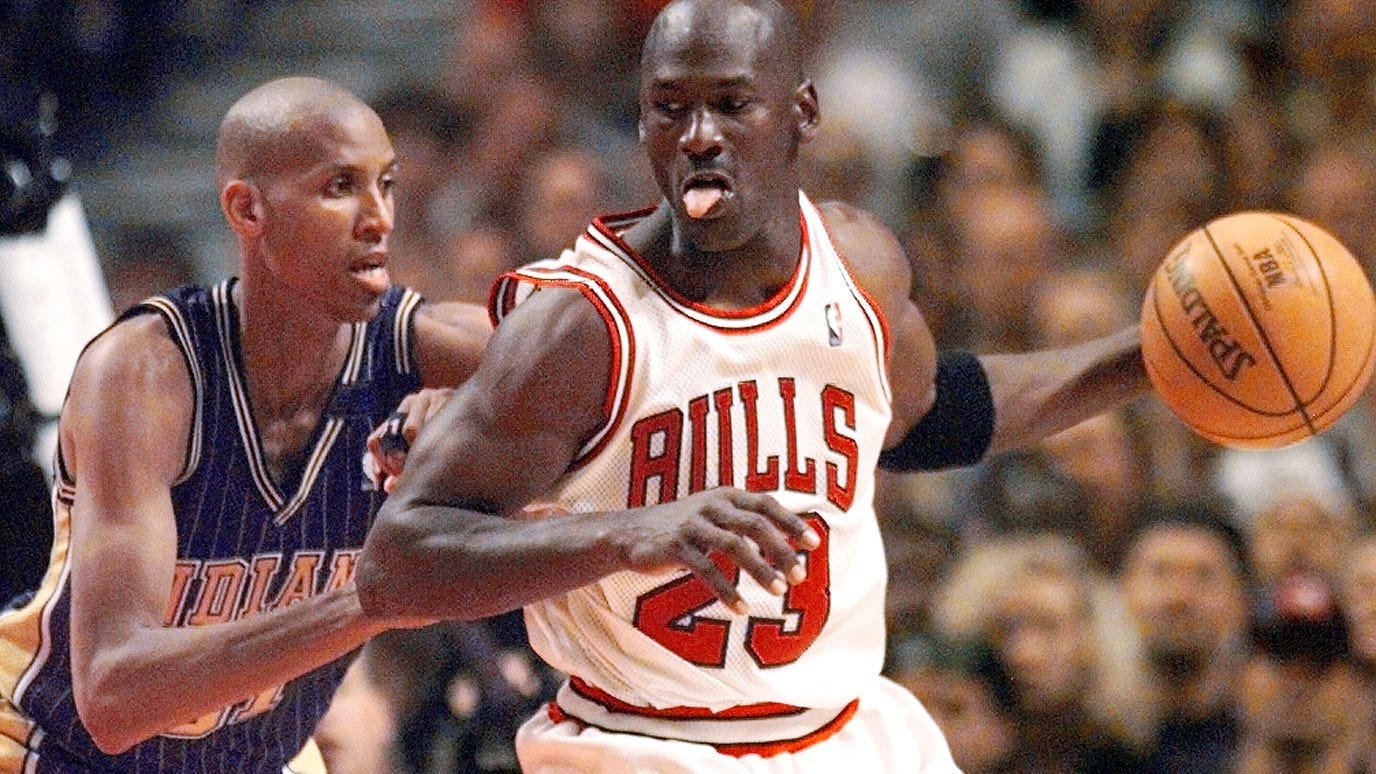

Nike had Jordan and owned aspiration.

adidas had heritage and global credibility.

Reebok had Shaq and Iverson.

Converse were still hanging on.

From the outside, there didn’t seem like much room left.

But that assumption only held if you believed basketball culture lived exclusively in the NBA.

One brand didn’t.

They knew they couldn’t win a traditional, head-to-head fight for leagues, stars, or endorsement power.

So instead of competing harder in the same lane, they competed somewhere else.

They changed the battlefield.

The insight.

AND1 followed one school of thought. It was simple, but radical at the time.

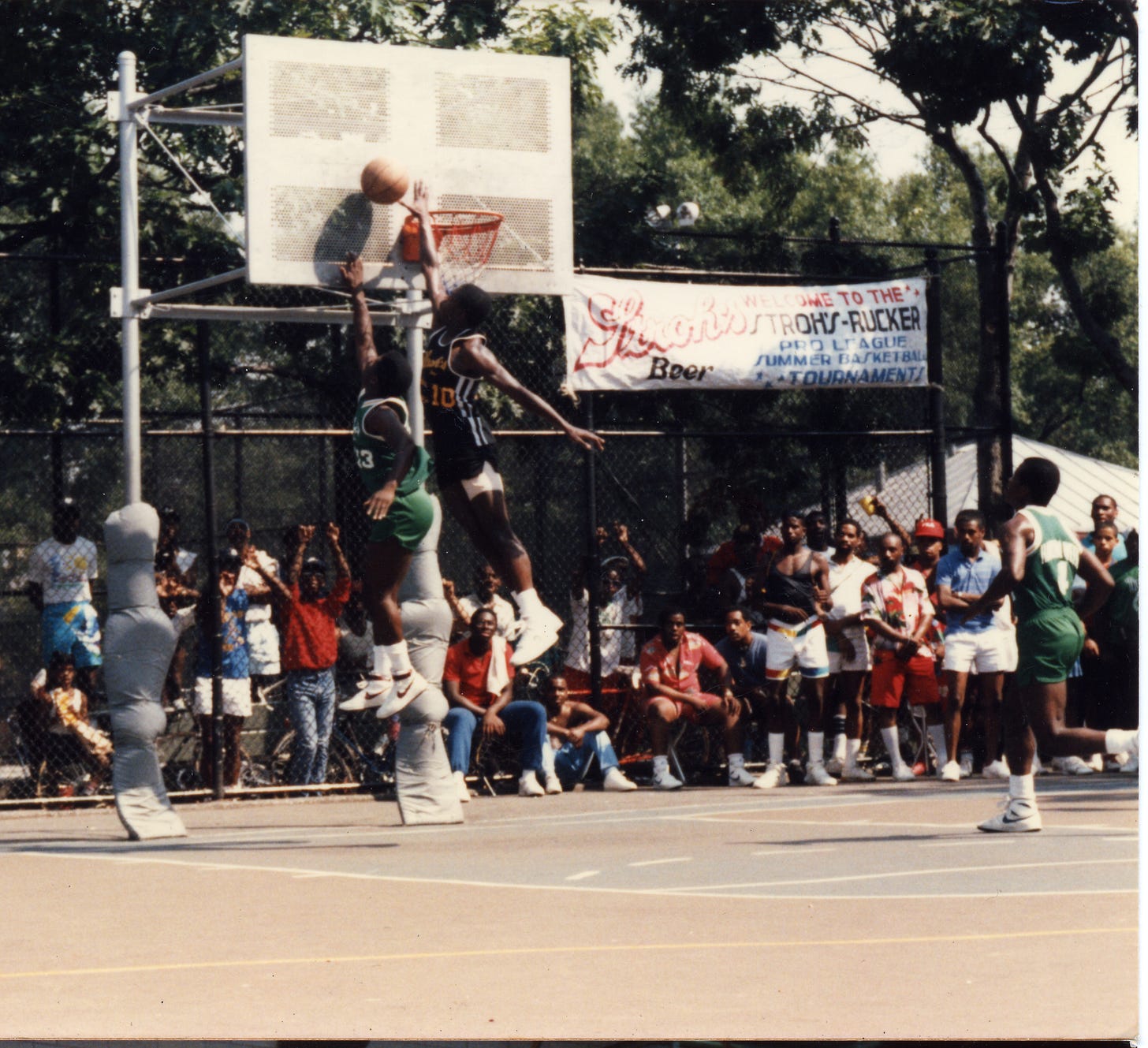

Real basketball culture lived on the blacktop, not the hardwood floors.

The NBA was polished and controlled, with the occasional exception like Rodman and soon to be Iverson. It preached the best of the best.

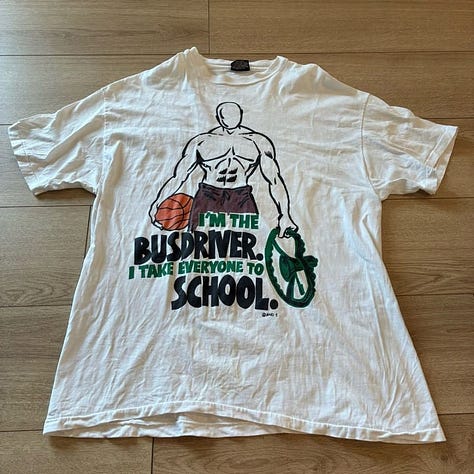

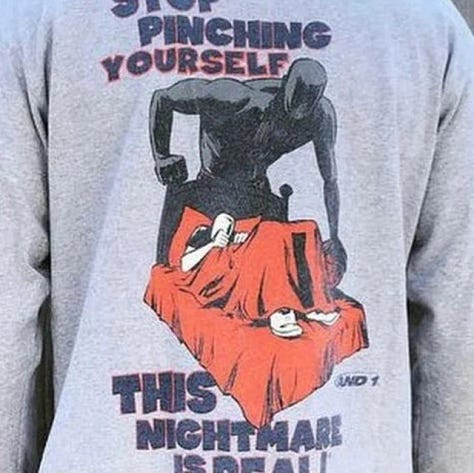

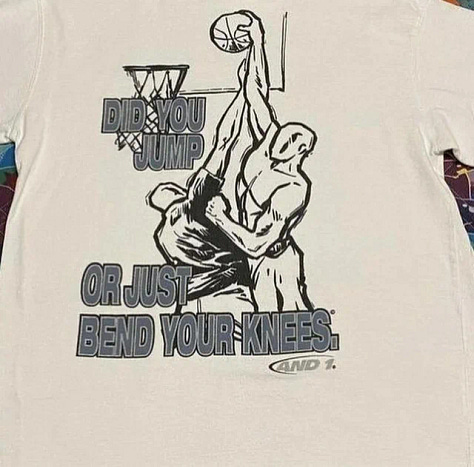

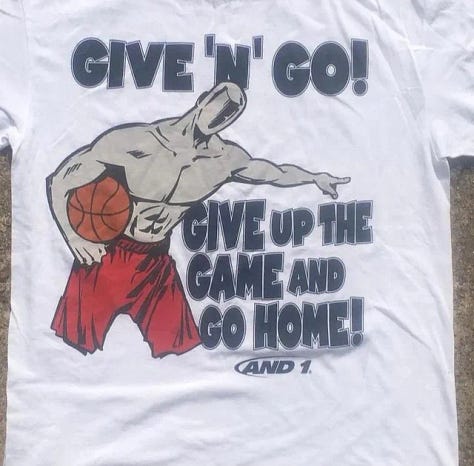

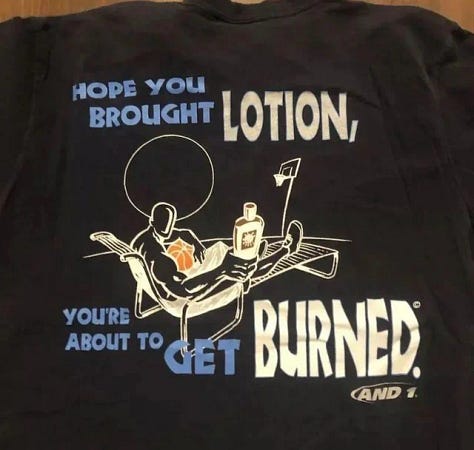

Outside, though, streetball was raw, expressive, disrespectful, local, and unforgiving.

More importantly, no major brand had made it their focus.

Streetball was treated as a carry-over from owning the NBA, not a culture worth owning outright.

That gap was the opportunity.

The positioning.

Nike celebrated greatness.

AND1 celebrated attitude.

Nike’s world lived under bright lights.

AND1’s lived on cracked concrete.

They weren’t building for fans watching from the bleachers at Madison Square Garden.

They were building for the ones running it back every day at Rucker Park.

That single choice shaped everything.

Not polished.

Not corporate.

Not exclusive.

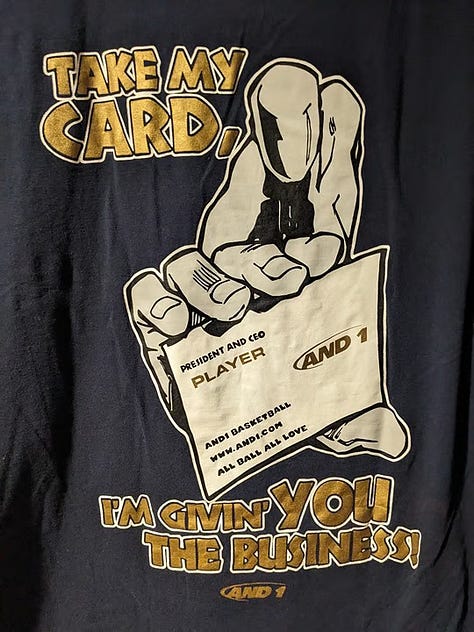

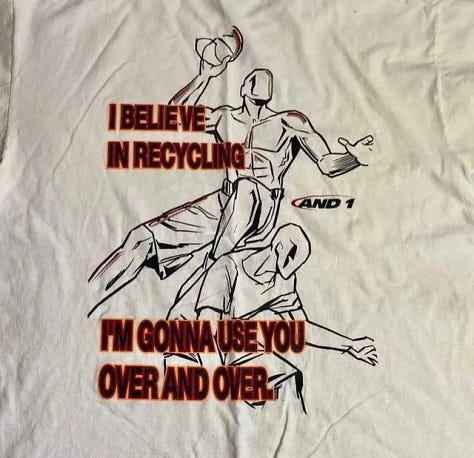

They spoke in court language, not corporate manifesto presentations.

That language mattered because it didn’t explain itself.

If you knew, you knew.

If you didn’t, it wasn’t for you.

The strategy.

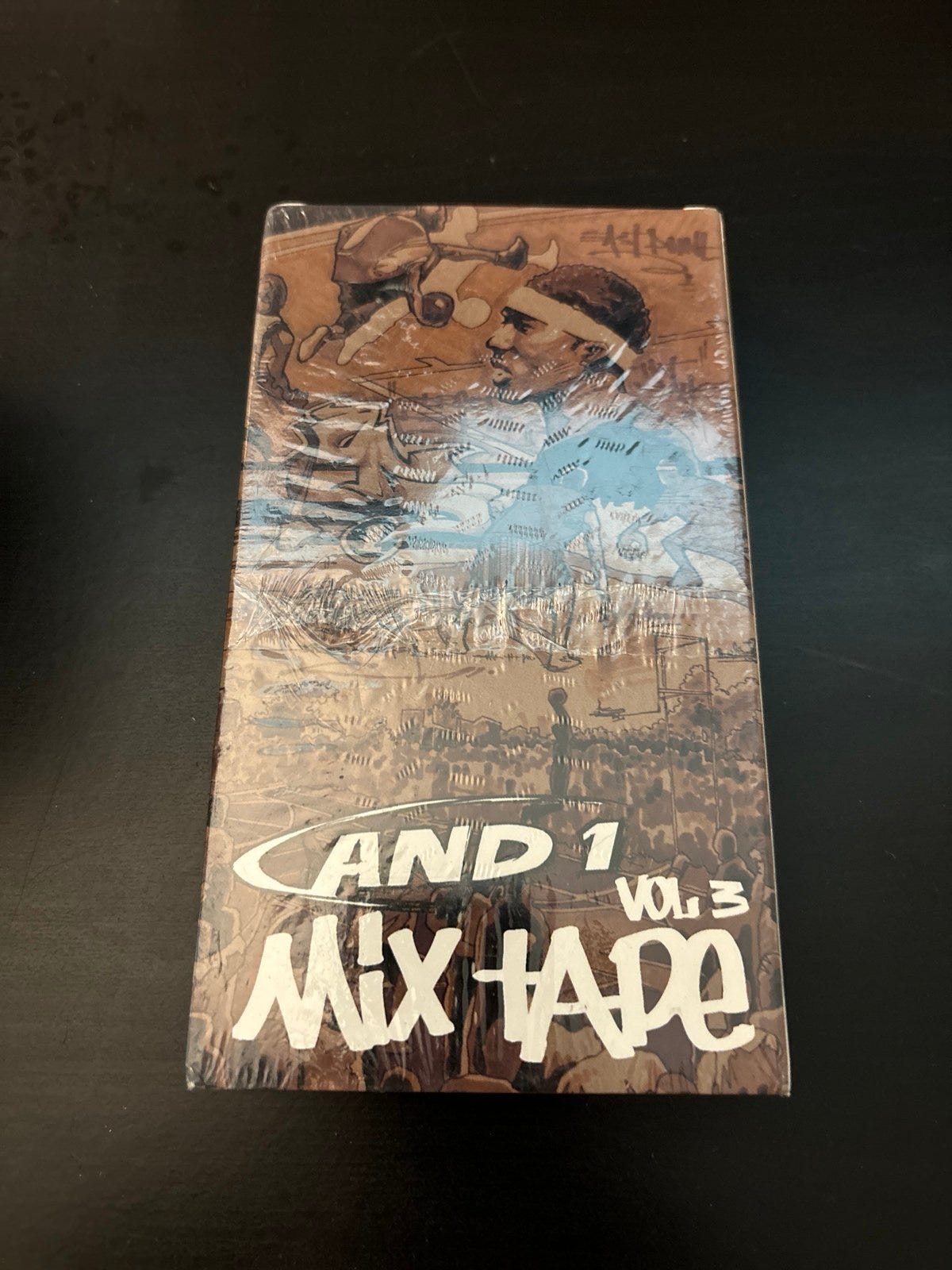

Before content marketing was even a thing, AND1 unlocked growth through mixtapes.

Instead of ads, they distributed VHS tapes, yes actual video tapes, hand to hand.

Instead of blowing budgets on NBA stars, like Skechers is doing, (trying and failing now) with Embiid, they elevated street legends.

This did three things:

It made AND1 feel discovered, not sold.

It created heroes the mainstream didn’t control.

It turned the audience into distributors.

The Mixtape Tour later became a live, travelling embodiment of the brand.

A cultural event, not a campaign.

Back in Australia, these tapes were easier to get than NBA footage.

That mattered.

Accessibility was the differentiator.

Nike didn’t want you to be anything like their stars.

And realistically, only a tiny percentage of people ever have a real shot at that level.

AND1 didn’t ask for that.

If you could hoop, and could hold your own against the neighbourhood, you belonged.

For a 12-year-old me with a decent handle, I was more likely to be an AND1 player than an NBA player.

I could practise the moves I saw on an AND1 tape.

I couldn’t practise being Like Mike, unless there was a trampoline under the ring.

That inclusivity made the brand feel owned by the community, not rented from it.

Nike felt aspirational.

AND1 felt like yours.

The lesson.

The lesson still holds.

Cultural relevance beats budget when it’s real and specific.

Going head-on with the top of your industry will never be a fair fight if you play their game.

So change the game.

Pick your lane.

Own what they don’t.

Make sure you actually mean something to the people you’re building for.

As always, thanks for reading.

Hayden

PS: A.O. was always my favourite.

“Hot Sauce” was the most outrageous, but A.O. felt like the perfect mix.

Creative, controlled, and the one whose game would’ve translated best to properly reffed games.